Additive Assembly for PolyJet-Based Multi-Material 3D Printed Microfluidics

Elzabeth Childs, Andrew Latchman, Andrew Lamont, Joshua Hubbard, Ryan Sochol

PolyJet-based additive manufacturing (3D printing) allow for micro-to-mesoscale fluidic systems to be produced with multiple, fully integrated materials and unparalleled geometric versatility. Although the PolyJet 3D printing process is autonomous and fast, the post-processing methods required to remove the sacrificial materials can be exceedingly time-intensive for systems with enclosed channels, often resulting in device degradation. To bypass such issues, here we present a novel “additive assembly” strategy for realizing PolyJet-printed multi-material microfluidic components. In this work, we print a microfluidic capacitor (which acts as a balloon to hold fluid akin to an electric capacitor holding charge) as two separate halves to enable facile support material removal, and then fasten the parts together via designed integration features. Fabrication results revealed a significant reduction in post-processing time by approximately 98% compared to enclosed control designs. Experimental results for burst-pressure testing – a measure of component integrity – revealed that the additively assembled microfluidic capacitors retained a maximum internal pressure in excess of 189 kPa before failure. The results suggest that the presented additive assembly holds promise for greatly extending the utility of PolyJet 3D printing for microfluidic applications.

Concept and Design

The additive assembly methodology in this work consists of five key steps. First, a 3D model of a microfluidic system is sectioned into separated components such that any and all internal channels become unenclosed. As shown in figure above, an enclosed microfluidic capacitor would be divided into two unenclosed halves. The capacitor would be printed with flexible (shown in black), rigid (shown in white), and sacrificial support (shown in yellow). Features that promote flexible-to-rigid interactions akin to O-rings and fastener elements are added along critical points for optimal fluidic sealing. The resulting parts are then PolyJet 3D printed with the unenclosed channels facing upward, such that the sacrificial support material is never deposited into the unenclosed channels (Fig. a). Next, the water-soluble support material is removed from the parts (Fig. b). Lastly, the fasteners with string-like extrusions – all printed in place (Fig. a,b) – are used to align the parts and then tightly seal the final assembly (Fig. c). Thereafter, the part can be used for microfluidic operations (Fig d).

Results

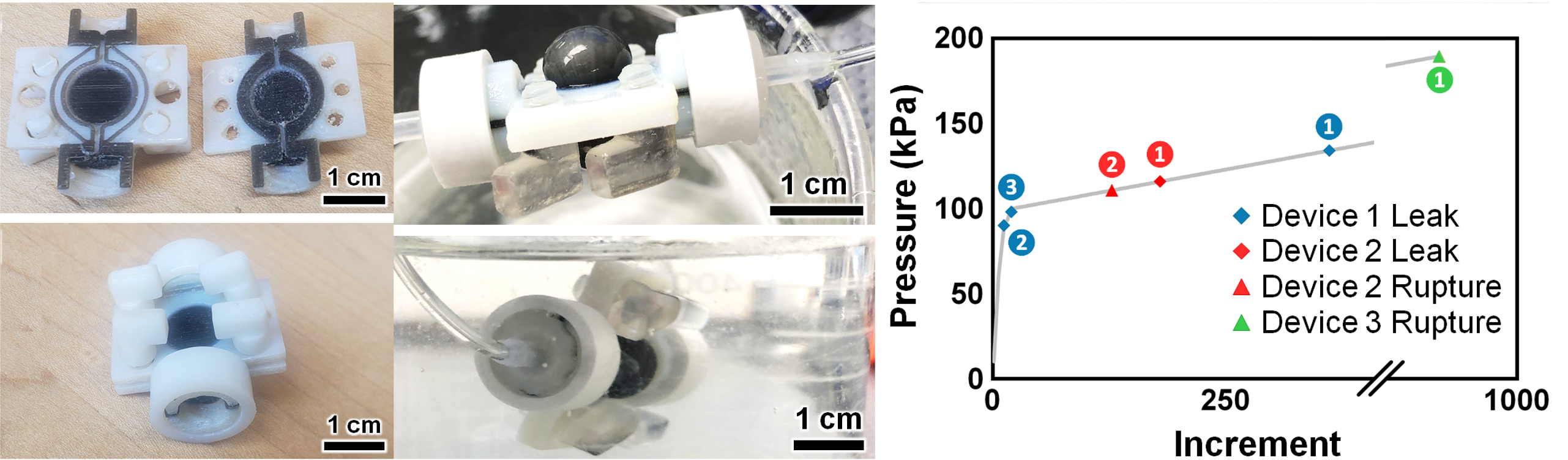

To investigate the sealing efficacy of the additive assembly strategy, we aligned the distinct PolyJet-printed parts, assembled them into a singular component using the printed fasteners, and performed burst-pressure experiments with three distinct devices. The resulting capacitor is shown in the left on the figure above before (top) and after (bottom) assembly. Once assembled, the microfluidic capacitor design results in visible inflation of the flexible diaphragm under an applied input pressure, as shown in the middle image (top). For the burst pressure test, each device was submerged in water (bottom) and monitored for two types of failure modes resulting in visible leakage (i.e., air bubble generation):

- assembly-associated leakage (from locations where the two distinct parts interact)

- diaphragm leakage/fracture, which is unrelated to the additive assembly process

Experimental results for the first device initially revealed effective assembly integrity for pressures up to 134 kPa; however, subsequent trials failed at lower pressures of 90 kPa and then 98 kPa (Right figure: blue data points. Note the numbers indicate the inflation pressure trial). A second device first exhibited assembly-based leakage at a slightly lower pressure of 116 kPa, but then maintained assembly integrity until one of the diaphragms failed at 111 kPa during the second trial (Right Figure: red data points). Experiments with a third device did not reveal any failures due to the additive assembly process as the device maintained internal pressures in excess of 189 kPa at which point a diaphragm ruptured (Right figure: green data points.). Despite differences in designs and printed material properties, the additive assembly results correspond to comparable and/or higher pressures than those reported in prior works for fully enclosed inkjet-printed 3D microfluidic capacitors (See paper for more details).